"TRANSLATED PEOPLE" : MICHAEL PARASKOS* ON GIORGOS CHRISTODOULIDES POETRY

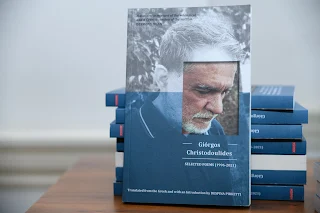

Book launch of “Giorgos Christodoulides: Selected Poems (1996-2021)”, translated from the Greek and with an Introduction by Despina Pirketti, on Tuesday 5 April, 6:30pm, at the Cyprus House, 13 St. James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LB.

by

Michael Paraskos

I am going to begin with the poem Smithereens.

Smithereens

In the moment

when the cup falls to the floor

and smashes into a hundred shards,

you realise the value of wholeness;

that what we call entire

is on the verge of smashing —

it is that which resists falling

and breaking into one hundred shards,

that which persistently withholds

the sum of its parts,

determined not to let on

that it is as brittle

as a cup

it is

exactly that:

one hundred shards clinging firmly

to each other

to feign unity.

I must admit I have become very fond of that poem. But really I wanted to begin by reading it because I think any talk on a poet should start with the poet. Or perhaps I should say with the poetry. Doing that places the poetry at the heart of whatever the commentator — in this case me — is likely to say next, and reminds us that we are talking about a work of art that is — or should be — complete and immanent. It is its own interpretation.

That is not to say that I am not honoured to have been asked to add my commentary to Giorgios’s work. I spend my life as an art historian adding my commentary to other people’s work, even though I know it often does not need it. Yet, when Despina asked me to speak tonight I was reluctant. ‘I don’t read Greek,’ I said, but that’s alright, it’s a translation she replied. ‘But I’m an art historian, not a literary critic,’ I said, but she said that’s alright, we don’t want a literary critic. ‘But I am probably going to say something rude and offend everyone,’ I said, but that’s alright, said Despina, we want you to be rude and to offend everyone.

Okay I made that last bit up, Despina didn’t say that, but I do suspect that what I am about to say might offend some people. But if that’s the case, then I think it’s probably the sort of people who deserve to be offended.

So here goes. The real reason I was reluctant was not any of the excuses I gave to Despina when she first asked me to speak tonight. The reason is that, as a member of what is rather euphemistically called the Cypriot, or Greek if you prefer, diaspora I have a difficult relationship with Cyprus. I do not always like the place. It has never felt welcoming to me in the way it likes to portray itself. Other people may have different experiences to mine, but I do not feel Cyprus is welcoming for so-called second-generation Cypriots like me. We’re not Cypriot enough; not Greek enough; not anything. We are, in a sense, some of the hundreds of shards who do not cling firmly to the whole. But the whole doesn’t seem to care.

Even as I walked into the graveyard, in the village near Larnaca, when we were burying my father following his death in 2014, someone thought it appropriate to berate me for not being a proper Greek. Not being fully Greek. What a nasty little shit you are I thought. And so much for being part of the global Cypriot family that places like this claim to promote. It was then I decided not to pretend to be Cypriot, let alone Greek, any more. It is easier to deny it outright, although my name sometimes makes that difficult.

The coastguardsman on his return

When I discovered the existence of language

I began learning beautiful words;

I learned quite a lot, but they seemed inapplicable.

The people I found worthy

were much fewer than the beautiful words.

The redundant ones

I kept within poems

as a collector keeps pressed carnations

within cardboard boxes

or the coastguardsman on his return at night

entombs a shard of glow from the lighthouse

inside of him

to light up in good time.

So why would I want to talk about a book of Cypriot poetry?

Well, perhaps because, whether you like it or not, or I like it or not, I am a Cypriot. I am a shard from that pot. In fact I must be a Cypriot because I have a piece of paper in my wallet that says so. I might not fit your definition of a Cypriot, your definition of a Greek or a Greek-Cypriot, but so what? Do you really think you matter so much? And so when Giorgios’s poetry becomes available to me, and the thousands of people like me, as in Despina’s translation, maybe I do have something to say about it. In fact, maybe as a translation, it speaks even more to me, and the thousands of people like me, the second and third generation Cypriots, the diaspora. We are, after all, each of us a translated poem.

But then the question is, what does it say to us? Well, I can only speak for myself.

A short while before the covid pandemic hit I was asked to speak at another book launch, held at Leeds University, for a newly published volume of poetry, that time by the English poet Martin Bell. I say by Martin Bell, but in fact it was also a collection of translations, made by Bell of the work of the French Surrealist poet, Robert Desnos.

Bell died in 1978 and has been somewhat unjustly forgotten in the decades since. I was asked to speak because Bell had been a good friend of my father, and they had travelled together to Cyprus in 1968, when my father was laying the ground-work for establishing the first art school in Cyprus, the Cyprus College of Art. Unfortunately Bell was a notorious alcoholic and his drunken antics did not go down well in the very conservative world of late-1960s Cyprus. This trip was recorded by my father in a diary, and it was part of that diary I read out.

I must admit I felt bad about it afterwards. I realised that what was intended as a lighthearted anecdote about Bell’s drunkenness on an unsuccessful trip to see the British Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, who was holidaying in Kyrenia, might in fact have been a painful recollection of Bell’s alcoholism for his family in the audience.

However, my point in mentioning this now is not to seek absolution for my unintended sin, but to bring Bell’s Cyprus poetry into the fray. Despite his alcoholism, Bell still wrote very good poetry, including some astonishing poems written whilst in Cyprus. They are different to his other poetry, and I suppose my father would have said they have spirit of place. We might like to think of them as somehow capturing the Cyprus that existed then, a very different island, and in many ways inhabited by a very different people, to the Cyprus that exists now. Those Cypriots would be as alien to modern Cyprus as I am. But I don’t think that is quite adequate when thinking of Bell’s poetry. I don’t think he did capture Cyprus, like some sapient literary camera. I think he captured himself-in-Cyprus, in a brief and specific moment of time. His poems do not look outward, recording a scene accurately. They look inward, and we see in them the experience of being trapped perpetually, somewhere between drunkenness and hung-over, in that hot sultry summer of ’68 in the eastern Mediterranean.

Rather than a moment of capture then, I think they represent a moment of placement. Or, if we want to sound a bit more intellectual, a moment of emplacement. There is a kind of emplacement in Giorgio’s poetry too. It is also set in Cyprus and aspects of that Cyprus are recognisable to me. But still, it is different. It has to be. We may share certain common traits, the things that make us human and we share a great deal of common culture, the things that make us social. But the experience of our bodies in time and space is surely unique to every one of us.

Incarnations of the watermelon seller

He sells watermelons in front of the bus stop.

In his past life he too sold watermelons

though because in the 17th century

there were no buses,

he sold them next to horse and donkey dung,

at the crossroads of the dirt tracks

that joined the pastures.

One time he brought a juicy watermelon

to the court of the Regina,

didn’t win her favour.

He suspects that in his next life too

he’ll be

selling watermelons.

Only he’d like to be

younger,

less hunched

and better attired.

Passing by in my flying car,

I’ll see him

and write the same poem.

I wonder whether Giorgios would write the same poem. A different body in a different time and space you see. It wouldn’t be quite the same. The emplacement would be different. Nonetheless, I have come to like that poem very much. Seeing the watermelon sellers all over Cyprus in the early summer, sitting in every lay-by and at every road crossing, with their giant stripy green fruit piled high on the backs of pick-up trucks, one often cut open to reveal the shocking red flesh — crass, vulgar and yet delicious — is like a throw back to a Cyprus where these transient street-hawkers might have been joined by a pastellaki seller, a koupes hawker or a mahelepi pedlar. Of course, they have largely gone, so only the watermelon sellers remain. But I am not being nostalgic in lamenting their loss. I just recognise in it an essential truth that I also seem to read in Giorgios’s poetry. Cyprus can at times resemble a post-apocalyptic landscape, in which we might recognise some familiar sights, but there is also a feeling of profound loss and dislocation. That sense of dislocation is there even in the apparent whimsy of the poem about the watermelon seller. Indeed, to my ear there is nothing whimsical about it. I find it terrifying — almost like some Buddhist nightmare of eternal reincarnation. Or to make another analogy, the narrator and the watermelon seller in Giorgios’s poem might almost be characters from a Beckett play, again resembling shards of the pot who cannot, or will not, cling firmly to the whole. Or do I mean dislocated shards of the pot to which the whole will not cling?

The kiosk

Down the street

a kiosk closed.

It just shut down one day.

One morning it simply didn’t open

like a tired man departs

quietly and wilfully

for a one-way journey.

The kiosk owners vanished,

friendly and decent fellows,

we have never seen them again,

we maybe never will.

Now, every time I pass by,

I glance at the remains of things abandoned

inside the deserted store.

I look at the shape

of what has ceased to be

and I’m surprised to find

it doesn’t look at all like something absent.

Life,

when it goes away,

leaves something behind.

That thing lingers on, gathers

like fluff on the body of time —

and for a while it keeps death from expanding

to where there used to be

life.

I sometimes wonder if I have a morbid disposition. A tendency to see the solitary cloud on a sunny day and predict it will rain. After all, in The Kiosk doesn’t Giorgios give us a kind of hope, a feeling that something of life lingers on even after apparent death. A kind of trace-memory of life. So why am I drawn so much more to the first two thirds of this poem, where the bafflement at the sudden and inexplicable departure of the kiosk’s owners is so strong? As I say, it might be my own morose nature, but isn’t it also that, in that first part of the poem, we have the most human element? It is there we engage with the narrator’s inability to comprehend what has happened to the kiosk’s owners, and we discover they were 'friendly and decent fellows’. To me, the trace-element of life that lingers afterwards, ‘like fluff on the body of time’, sounds suspiciously like a sad and lonely ghost.

But perhaps Giorgios does not see it in quite those terms. I think we are similar insofar as we share a sense of that which seems whole is in reality on the edge of dissolution. Nothing is permanent, no matter how seemingly solid, no matter how good. But, unlike my own temperament, in Giorgios’s poetry dissolution does not necessarily lead to complete disappearance or total loss. Often something remains, even if it is not quite in the form in which we might want it.

In volumes

Just as the deceased

are placed reverently in coffins,

the coffins

in morgue chambers;

just as the pictures of the missing

are hung on police stations;

just as the skeletons

of prehistoric animals

are transferred to museums,

so too do poems

end up in volumes.

Giorgios’s poetic voice inhabits a world of chance encounters. In this he is the inheritor of a tradition that started with English romantic poets like William Wordsworth. Wordsworth’s poetic voice travels the Lakeland landscape of northern England, and runs into various characters, from little children who believe their dead siblings still live with them, to a pedlar who explains the reason for a cottage having been abandoned. In fact, I was reminded of Wordsworth’s poem The Ruined Cottage when I first read Giorgios’s The Kiosk. They are very different styles of verse, both of their times in a way, but they are linked by a sense of bafflement at the mystery of abandonment, and by an underlying sense that humanity is threatened by unseen and inhuman forces that have the power to sweep seemingly full and happy lives.

A kiosk closes. What does it matter? A cottage is abandoned. What does that matter? Well, maybe it doesn’t matter, such small bits of life when set against the grand scheme of things, there’s always another kiosk, always another cottage, always another pastellaki, koupes or mahelepi pedlar, always another watermelon seller, always another wilderness on which no one has built a condominium, always another beach on which rare turtles can nest, always another… until there isn’t another and you realise that unseen force, the deadly hand of human progress, has made our planet an inhuman wasteland. I think it is the shards of what was once whole and are now lost in a wasteland that Giorgios’s narrator encounters.

Poetry is often about the ability to find salient metaphors for life in otherwise seemingly unremarkable things. Think of the devastating conclusion Philip Larkin drew about lost hope in something as simple as failing to toss an apple core into a rubbish bin. Giorgios is good at finding those metaphors too.

The palm tree

As luck would have it, years ago

I found a palm tree thrown away

within my father’s orchard,

barely the size of a child’s open hand.

“No use in planting it,” he said,

“It’s clearly a waste of time.”

And yet I bowed and picked it up.

Now if you amble through my garden

you see a mighty palm tree

casting its branches over the fence

and singing all the while.

So when

they ask me of my kids I say:

“I have five and one almost died.”

I do like those lines, “casting its branches over the fence / and singing all the while.” Yes, trees do sing as they sway in the breeze, but it evokes much more than that. It evokes something joyous about life, especially about life so nearly lost. The tree sings because it is happy to be alive.

Who said I was morose?

It is this kind of metaphor-laden language that Giorgios uses so well. That does seem to be — I am going to say a Levantine or Mediterranean trait, rather than a uniquely Cypriot one — in which the mundane and the metaphorical meet. It is a trait most of us will know from the most famous book to be written in this region The Bible, but it imbues the wider Mediterranean and Levantine story-telling tradition too. I have found it has become an integral part of my own writing practice, both as an art historian, where I suspect it has not gone down well in the often hidebound world of academia, and in my fiction writing which has been enriched by it. I suppose that is another thing that makes me Cypriot, because — as Giorgios’s also writing shows — I find Cyprus is a land that constantly gives you metaphors for life. Like the time I was driving from Larnaca to Paphos and I decided to leave the motorway at the Yeroskipou exit to avoid going through the centre of town.

On the road that runs through the flat farmland between the motorway and the sea I saw an open-back pick up truck in front of me. In it stood a dog, a kind of pug or French bulldog, surrounded by her puppies. The dog was agitated, barking frantically, but the driver of the pick up truck just drove on. What he hadn’t realised was that one of the dog’s puppies had fallen out of the back of the truck and it was now running for its life along the road after its mother and siblings.

Driving behind it, I slowed to a crawl and began flashing my lights furiously to get the truck driver’s attention. Eventually he did stop. He got out of his truck, saw what had happened, and when the puppy reached him he picked it up, gave it an embrace and put it back into the truck where it was welcomed by its relieved mother. The truck driver gave me a cheery wave as a thank you, got back in his vehicle and drove away.

Even at the time that felt like a metaphor for something.

I think it is that ability to see the symbolic — the metaphorical — in the everyday that is such a strong feature of Giorgios’s writing.

Senex Rex

Outside the house next to the school,

there sits an old man.

He comes out at noon,

when the sun is shining,

on his crutches.

He sinks into his shabby armchair

like a weary king;

takes in the sun,

the agitation of giggles,

feigns a smile, but seems bothered.

He looks like a man at the end

of his tether.

I am fixated on him.

There’s nothing more interesting here.

On days whipped by cold, he withdraws,

retreats deep inside the house,

to the kitchen perhaps, with an oil stove

burning under the floor,

in the secret lair of his youth.

His wife closes the shutters tight

and double locks the doors.

Perhaps she thinks that death might

think twice,

and that with the next shaft of sunlight

the old man will rise again and reign in his court

from his aged armchair.

But death knows all his tropes.

It’s been a while since I last saw

the old man reigning in his courtyard.

How often I wonder will many of us here tonight have seen that old man sat outside a house or old shop somewhere in Cyprus, seated on ‘his shabby armchair’. When I read this, part of me thinks of my own father, Senex Rex, and especially of my mother double locking the doors. It has the authenticity of the familiar, the almost mundane. ‘There’s nothing more interesting here,’ the narrator tells us. But the poem also transcends familiarity, to become something metaphorical. A meditation on the passing of time — perhaps also on the way the world we inhabit seems to shrink — and on the inevitability of death. Dare I say it, it’s a kind of King Lear in miniature.

But maybe I should end my talk in the tried and tested rhetorical fashion, by returning to where I started, to the question of translation, to the question whether I might offend some people. Translated poetry, translated people.

There is a story that in the 1980s, when the British establishment was just beginning to recognise that Britain was a multicultural nation, a British government department decided to produce a guide in various languages other than English on how to register to vote in local elections. Because of the large Greek-Cypriot community in Britain one of those languages was Greek, and so a civil servant who said he was able to speak Greek was given the task of translating the complex set of instructions on how to get your name onto the electoral roll. Once complete, the translation was duly printed and distributed, but soon reports started to come back that there was a problem with the Greek guide. It was said none of the Greek speakers who requested it could understand a word of it. An investigation followed, and it was soon discovered that the civil servant who had made the translation could only read and write the ancient Greek he had learned at Oxford. Perhaps from that we should acknowledge that even modern Greeks might be translations of the original.

But of course no one wants to hear that, because it’s too easy to dismiss translation as a second-best version of the original. But I think that’s a very blinkered view. Sometimes translations can go beyond the original. Take the British Empire. Whatever one thinks about the legacy of that Empire, a legacy that is so often so negative, there is no denying the English culture that underpinned it is an astonishing thing. The civilisation that gave us the colonial horror of the Amritsar Massacre, is the same civilisation that gave us King Lear. But what I find more astonishing still is that the English culture that gave us King Lear is a culture built on translation. And a very specific translation at that. It is built on the translation of the Bible into English by William Tyndale in 1536. Without that translation coming into being it is hard to imagine English culture as we know it existing at all. The language of that translation, so beautiful and charged with additional meaning, was the engine that powered the work of almost all English writers who followed it, from William Shakespeare to T. S. Eliot and beyond. There’s nothing second best about it.

In fact, one of my favourite English poems is one I first learned at university, and it is a translation. Written by Thomas Wyatt in 1557, it is called Whoso List To Hunt, and it is a translation from an Italian original by Petrarch. Of course there are now better translations of the Petrarch original — better in the sense they are more accurate and no doubt more emblematic of Petrarch’s original intentions. But none of them are to my mind as mournful and haunting as that by Wyatt. It too is not second best.

And I, as a translated person — the product of two voices coming together, just like a translation, my English mother from Yorkshire, and my Greek father from Cyprus — I also refuse to be called second best. If that’s what you think I am, I don’t care. You do not matter that much.

Those who know me will be aware I have studied a great deal the work of Herbert Read over the years. Herbert Read was a poet, novelist, art theorist, educationalist, anarchist and more. He argued that to survive human society needs art because the function of art is to reconcile the myriad of seemingly distinct and separate forces we encounter in life, and that through the ongoing and continual process of that reconciliation, or hybridisation, our understanding of reality is brought into existence. In other words, the shattered shards are reconciled. And I cannot help seeing the translation of poetry as something very like that. It is a kind of mystical union, a reconciliation between the poet and the translator. The product of that union might not be pure any more, it might not be pedigree, but sometimes, to echo Giorgios’s poem Smithereens again, it is more than the sum of its parts. And in that I suppose we might almost say a translation is the product of a marriage, it is the child of two parents, it is the offspring of the poet and the translator.

I hope you will enjoy reading Giorgios’s poetry as much as I have done. As an art historian I study paintings and sculptures and other works of visual art in a great deal of detail, and this year is my thirtieth year working as a lecturer in higher education, so I have also spent a great deal of time over those years talking about art and trying to give my best guess as to what it might mean. In all of that time I have not had so much opportunity to think long and hard about poetry, although it was my first love as an undergraduate student. So, despite my initial trepidation in giving this talk, the process has been a welcome chance to do that. It will probably sound a bit trite for me to claim this, but I can honestly say I feel changed at having spent so much time reading, re-reading and thinking about Giorgios’s work, so much so, that it has even entered my dreams on a number of occasions. As I say, I feel changed by it, and that change is, I think, for the better.

So I would like to thank Giorgios for writing these wonderful poems, and Despina for translating them. They are your children and I think you have every reason to be proud of them.

*Michael Paraskos is a Senior Teaching Fellow in the Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication at Imperial College London

Σχόλια

Δημοσίευση σχολίου